By Derek O’Brien

A tribute to the quintessential Quiz Master of all seasons in the form of, what else, a quiz

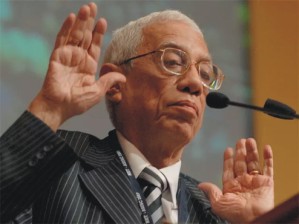

It was on this day four years ago that my father, Neil O’Brien, left for the Big Library in the Sky. As a man always surrounded by books – as an author, a publisher, an educationist, an unceasing, unresting and inquisitive reader who converted his formidable knowledge to quizzing success – I like to imagine that Dad’s idea of heaven was a large room filled with shelves and shelves of books!

For four years, I have largely remained silent about my father. I have grieved for him and I think of him – and of my mother, Joyce, who joined him one-and-a-half years ago. – almost every day. Yet, I did not speak at the memorial service, leaving my more articulate brothers to deliver the eulogies. I did not contribute to the wonderful book of stories and remembrances, with lovely pieces by Neil’s friends and family, that we released soon after he left us.

I was fortunate that my father was well-known and well-loved in our city. Neil loved Calcutta as few have, and his city loved him back. Part of the problem in writing about him is that he is such a familiar figure to just so many people in the city, and in the rest of the country. There is very little I can say about him that others have not already said. Nevertheless let me make an attempt, and give you five facets to Neil O’Brien that you probably didn’t know. Let me also do something typical of him, and frame each of these as a quiz question.

This is doubly appropriate because he was among the founding columnists of TheTelegraph. The Sunday quiz column that began in July 1982 was a passion for him, with Neil going through hundreds and hundreds of postcards and inland letters sent by readers across the city, across Bengal and further afield, with questions to share or something to ask.

1. Which calling was Neil contemplating till he met the woman in his life?

As a shy young lad, Neil had a nerdy, bookish existence, with occasional excitement on the hockey field. He was a regular at church though and frequently did duty as an altar boy. At St Xavier’s, a Belgian Jesuit priest, Father John Biot, became a mentor – on the sports field, on the stage, and in offering spiritual guidance.

Father Biot was particularly impressed by Neil’s learning of Latin, so much a part of Catholic ceremonies, and encouraged him to consider entering the clergy. Neil was strongly inclined till one day, at the age of 21, he met Joyce at a party. It was love at first sight and God helped him make up his mind. Father Biot attended the wedding and blessed the couple.

2. How did a lightning call to Madras (now Chennai) change Neil’s life?

It was 1977, and a new government had just come to office in Bengal. Neil was in the city we now know as Chennai for a business visit when two of his close friends, both associated with the new ruling party, dropped in and asked Joyce where Neil was. It was an urgent matter and couldn’t wait; the chief minister wanted to see him.

She shrugged her shoulders and said he was travelling and would be back in a couple of days. Those were times before mobile phones. In fact we didn’t even have a landline at home. Joyce would only hear from Neil when, as had been pre-arranged, he would dial a neighbour’s landline from his hotel, late in the evening.

The two gentlemen were in a hurry and asked Joyce to phone them as soon as Neil contacted her, and to get his hotel phone number. Neil’s whereabouts were duly traced late in the evening and a lightning call was booked. His friends told Neil that he had to rush back immediately as he was going to be nominated to the state assembly as the Anglo-Indian MLA. “Me?”, he said incredulously, “not possible. I know nothing about politics. Besides I have my meetings set up for tomorrow and certainly can’t come now. Find someone else.”

It took a lot of persuasion for the gentlemen to convince Neil that they were serious. He reluctantly agreed to change his tickets and come back earlier than planned, but only after he had kept his appointments in Chennai. On his return, he went off to meet the chief minister, a fellow Xaverian. And so began a three-term stint in the state assembly, which ended when he refused a renomination in 1991.

3. Why did Neil sit in a room in a church on Ripon Street three evenings every week?

Neil had friends from all walks of life, all religions and all backgrounds. He never saw himself as limited to the Anglo-Indian community, though of course he had many Anglo-Indian friends and associates. When he became MLA for the community in 1977, he came face to face with the diversity of the significant Anglo-Indian population in Bengal. There were dimensions and challenges he had not experienced or even known. He was now expected to provide solutions.

As he wondered how to go about it, Joyce gave him excellent advice: “Meet and listen to people and their problems. That’s the best way.” There was wisdom in those words. Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, after work, Neil and Joyce would go to St Mary’s Church on Ripon Street and meet folks from the community. Senior citizens battling land sharks; a broken marriage; alcoholism in the family; a young man’s quest for a job; a teacher seeking career advice for herself – Neil listened, engaged and tried to help. Joyce and he were the last to leave, after meeting everyone who had come that day.

The interactions formally continued from 1977 to 1991, but actually extended till his very death. They gave Neil an unmatched insight into the community. He made himself useful to literally thousands of families. “I saw Anglo-Indians at their best,” he once told a friend, recalling those evenings at St Mary’s, “and I saw them at their worst.”

4. Why did Neil turn down a chance to enter the Lok Sabha in 1991?

Till recently, two Anglo-Indians would be nominated to the Lok Sabha after each general election. This was a Constitutional provision. In 1991, the lawyer Frank Anthony, who had seen Neil blossom as a leader of the community from Bengal, gradually making his name nationally, decided to step down as long-standing MP. He was getting on and recommended Neil.

Neil spoke to his employers at Oxford University Press. OUP had been virtually family since the mid-1960s. Publishing was Neil’s natural home. He had a degree in economics and an MA in English literature. He was a voracious reader and keen editor. He had begun in sales and knew the commercial aspects of the business as few did. He was the perfect all-rounder and an obvious prospect for the top job. If he became an MP, however, OUP could no longer consider him for the managing director’s position.

That was it. The MD’s role in OUP meant much more to Neil than becoming an MP. He met Frank Anthony and senior people in the government to convey his polite refusal. Frank Anthony was surprised but, I suspect, also proud of his protégé. It was only in 1997, when Neil had retired from OUP, that he finally entered the Lok Sabha.

5. Why did Joyce call Neil her “Bengali husband”?

In very many ways, Neil was very Bengali in his habits and instincts. It was part of his upbringing, brought up in Jamir Lane by his Bengali doctor grandmother who taught him the local language as a child. This middle class Bengali neighbourhood was his home all his life; here he was always “Neil da”, never “Mr O’Brien”.

His food habits were tellingly Bengali. He loved fish but Joyce, the devoted wife, had to painstakingly pick the bones for him. Like so many Bengali husbands, he depended on the Mrs to choose his clothes and pack his suitcase before he left for a work trip. He had no idea what was inside.

Christmas Day saw an open house at Neil’s and Joyce’s. Many dishes were cooked, but the centrepiece of the Christmas lunch was Bengali-style chicken curry, dal and Gobindobhog rice … Maybe that’s what I’ll have for lunch today – rice, dal and Bengali-style chicken curry with that signature aloo. Neil would be happy.

CTC- The Telegraph